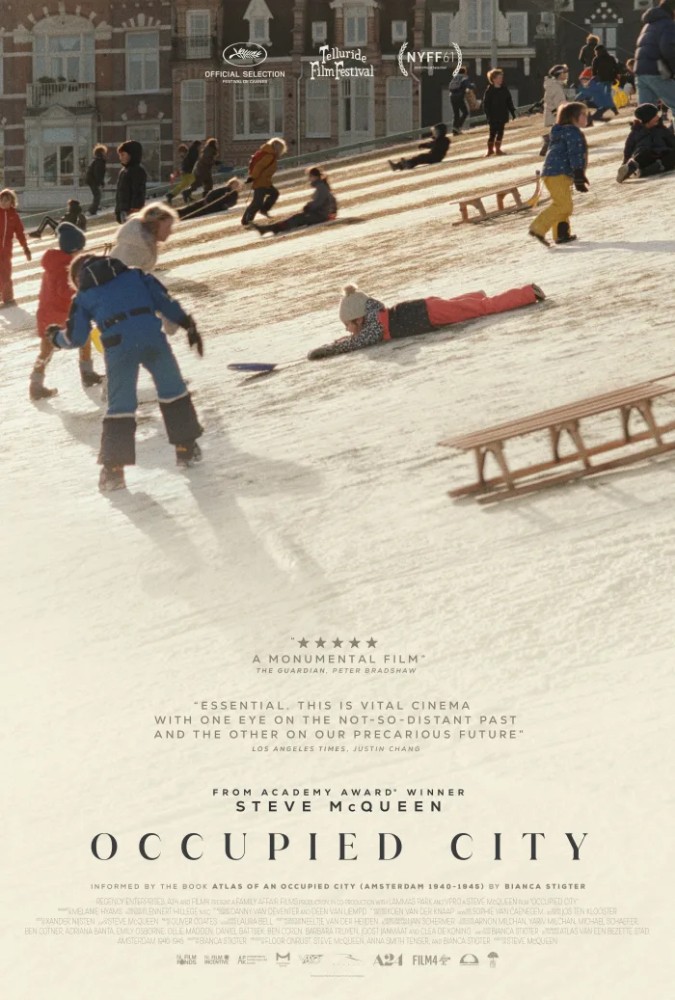

In a deeply personal conversation with filmmakers Steve McQueen and Bianca Stigter, they discuss the recurring themes of time, memory, and history in their respective work and in their collaboration on ‘Occupied City,’ as well as breaking the rules of traditional documentary filmmaking.

About Occupied City: The past collides with our precarious present in Occupied City, informed by the book Atlas of an Occupied City (Amsterdam 1940-1945) written by Bianca Stigter. McQueen creates two interlocking portraits: a door-to-door excavation of the Nazi occupation that still haunts his adopted city, and a vivid journey through the last years of pandemic and protest.

Steve McQueen is a British film director, film producer, screenwriter, and video artist. His film 12 Years A Slave received an Academy Award, two BAFTA Awards and in 2016 the BFI Fellowship. McQueen’s critically acclaimed and award-winning films also include Hunger (2008), Shame (2011), Widows (2018) and the anthology series Small Axe. Past documentary works include the BAFTA-winning series Uprising (2021). For his work as a visual artist, McQueen was awarded with the Turner Prize, and he represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2009. He has exhibited in major museums around the world. In 2020, McQueen was awarded a knighthood in the Queen’s New Year’s Honours List for his services to the Arts.

Bianca Stigter is an historian and cultural critic. She writes for the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad and published three books of essays. Stigter was an associate producer on 12 Years a Slave and Widows. In 2019 she published the book Atlas of an Occupied City. Amsterdam 1940-1945. In 2021 she directed the documentary Three Minutes – A Lengthening, which premiered in the Giornate degli Autori at the Venice Film Festival and was selected for the festivals of Telluride, Toronto, Sundance, as well as IDFA and DocA- viv. It won the 2022 Yad Vashem Award for cinematic excellence in a Holocaust related Documentary.

There is a haunting quality to Occupied City, hearing the emotionless voiceover text about the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam over images of contemporary life in Amsterdam. With encouragement from McQueen and Stigter I began this interview on a personal note, recounting when I saw the film at a recent press screening. Images of the neighborhood Apollolaan where my mother grew up, and the text about the Hunger Winter, the countless atrocities, including the many Jews forced into hiding, and the specific identification cards with the letter J stamped on it. My grandmother was among those in hiding, and she too had these documents, which I shared with McQueen and Stigter. I thanked them for allowing me the time to share this with them and expressed that this interview is not about my story, but about their film.

McQueen: It’s all of our stories. I don’t think you should leave yourself out of this interview; it would not be in service to your readers. It’s important to have this transparency. To be honest with you, it’s wonderful to add your experience into the interview because you’re a survivor of this situation.

Kouguell: Steve, in your interview with curator Donna DeSalvo in 2016 at the Whitney Museum, you discussed your installation piece End Credits about the Paul Robeson FBI files. The idea/theme of words being redacted, brought to mind not only the obvious government censorship but the idea of the literal erasure of history.

There is a thematic correlation between this work End Credits and Occupied City, and Bianca’s documentary: Three Minutes: A Lengthening Trailer. These works are historical investigations, which address the erasure of history, and the fragility of memory and time.

Stigler: What they also share is that you can find new forms to deal with the past and you don’t necessarily have to stick to the strictly well-known feature film or documentary genre, you can try to find a new way to convey history and the erasure of certain histories. And, also to make it more of an experience than a history lesson. There’s certainly common ground there.

McQueen: Both of us are very much about the audience and how things can sink in. With End Credits, it’s much more sculptural than Occupied City and Three Minutes, it’s for an art space due to the nature of its presentation.

Kouguell: Occupied City’s length of 4 ½ hours including an intermission requires a type of commitment from an audience. If it was two hours, for example, I don’t think the film would have the same impact. Steve, you mentioned that the film had to have the weight of time, the weight of recounting history, and to give the viewer time to reflect.

McQueen: Once people see the film, the length is never discussed. If anything, when it comes into discussion people wish it was longer.

Stigter: People said they lost any track of time. You enter a different zone of time, you don’t feel the clock ticking and you are transported somewhere else. One thing is for sure; you hear so many individual stories and you see so many people that you realize you can’t hear everyone’s story, then the film would have to be 100,00 times longer. It gives you a certain tension that no matter what you do, you can never know it all.

McQueen: It’s about the practice. It was the whole idea of using Bianca’s text, which occurred over 19-20 years of research, and projecting on that the every day. We never contemplated it to be shorter. When I was shooting it, I didn’t know what it was going to be, I had to find it through the process of filmmaking.

Kouguell: Bianca, in your film Three Minutes: A Lengthening, you made the decision not to show any contemporary faces except at the very end. We only see the three minutes of footage repeatedly shown and freeze frames of a home movie in 1938 Nasielsk in eastern Poland months before they were deported to ghettos by the invading Nazis.

With Three Minutes: A Lengthening and Occupied City you both made some unconventional choices in conveying your narrative, such as avoiding talking heads, and not including or only including archival footage from the past.

Stigter: In Three Minutes, it exists only out of archival footage from 1938. Doing things in this way makes you think about time more. With the other forms of documentary, people almost forget there are also forms; here you are asked to think about it.

Kouguell: Occupied City was shot over the course of 2 ½ years on 35mm film, and you had 34 hours of footage. With the exterior shots, did people know you were filming them?

McQueen: Most of the time people knew because the camera was there but sometimes not. It was the case of getting the everyday and wanting to be spontaneous.

Kouguell: Was anything staged? I’m thinking about the scene where the bicyclist hits a woman towards the end of the film.

McQueen: It just happened. Sometimes you have to predict the unpredictable.

Kouguell: There is a huge responsibility to the history of Amsterdam, the people of the past, and the present. Obviously you cannot include it all so the choices then become what to include or embrace, what to honor, what to leave out. How did you arrive at these decisions in Occupied City?

McQueen: We shot everything in Atlas of an Occupied City – over 2,100 addresses. When we had the footage, it was a case of certain things being repeated so therefore we could leave that out, and then we decided what was the best for that particular version. What flowed and what didn’t. We were fortunate to have this rich footage and situations to make this movie.

Stigter: When I was writing the book, the most harrowing part was when I couldn’t find any information about someone except that he or she was born and murdered, and that was all. If you can keep a little bit by telling about someone, there is at least something left instead of nothing. For me that was difficult to come to terms with; you can’t tell everything.

Kouguell: Bianca, I read that you referred to your book Atlas as “time machine on paper” – it’s a beautiful way to reference it.

Stigter: For me, it felt like that because you have a lot of history books that deal with the big picture or have the story of one person. What fascinated me was, could you imagine walking through a certain street back in that time so you knew things about the shops and the offices and the people that lived there; that you can get a sense of how something was in a different time and that fascinated me.

The strange thing about Amsterdam, in the city center, the canals, and so on, is that they are very much from the 17th and 18th century. You cannot see the Second World War and what happened there but you know it happened in the same spots where people were round up or executed, or took their own lives. The book and the film both try to cross that, while at the same time acknowledging that it is uncrossable. There are all kinds of tension between the past and present throughout the whole film.

Kouguell: What questions haven’t you been asked in previous interviews that you would like to address about Occupied City?

Stigter: The music; it’s very important for movies in general and in this movie, it is especially important.

McQueen: What composer Oliver Coates brought to the table was so transcendent; it brings another layer into the narrative, another echo in the audio sense.

Stigler: It makes it more abstract in a way but also grounds it very much.

Kouguell: What was then and what is now repeats for me. Ending with the bar mitzvah rehearsal and then the actual bar mitzvah was quite moving.

McQueen: We were invited to our friends’ son’s bar mitzvah. We thought it would be a good idea to shoot it. It was one of those things that everything in this movie is about our city; it’s about where we live, where our children go to school. We talked to the rabbi for permission.

In a way, it was to say that after all that, the Nazis didn’t win. There is a Jewish life that continues and exists in Amsterdam today. It was a very personal way to end the film. It’s about our family and our friends, and all of our futures.

Stigter: It’s beautiful and hopeful. It’s something fragile of course. We see and hear the boy’s voice trying to read the old words – it is very touching for me. It was also about not showing just the bad things but also the good things.

Kouguell: What has been the response to Occupied City from the Dutch audience?

Stigter: We had the Dutch premiere in the most beautiful cinema in the world, the Tuschinski theatre. The original owner was murdered in Auschwitz during the war.

McQueen: It was extremely special to have the premiere there and we dedicated it to him. It was a packed theater. You could feel the atmosphere was special to put this movie in this cinema.

Stigter: To see it in Amsterdam or another cinema, when you walk outside, I think one will have the feeling, I’ll look differently at my city now. In a funny way of course, people realize yes, that it’s very extremely local but it also has something universal. One can imagine this film in Paris or in London or New York. One can imagine the film anywhere.

Kouguell: Indeed. It is universal.

McQueen: Your background and history is amazing and thank you for sharing it with us.

Occupied City is in limited release in theaters and is available on most streaming platforms.