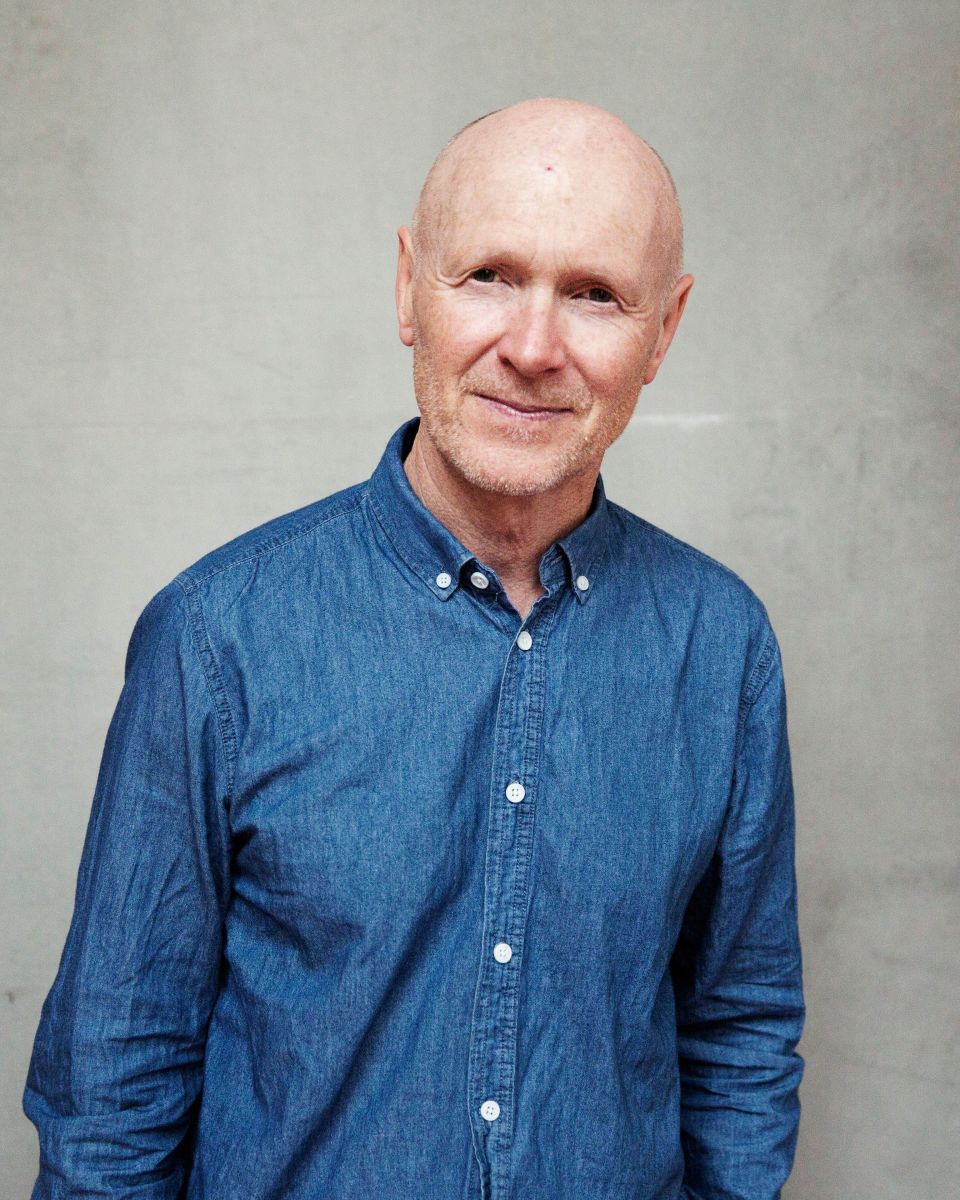

No two paths to a writing career are the same. Susan Kouguell interviews Austin Winsberg, writer, creator and executive producer of “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” on breaking in, working in the writers’ room, and growing a tough skin.

JUL 2, 2020

Click to tweet this interview to your friends and followers!

It was an absolute delight to chat with Austin Winsberg about his extraordinary career and his show “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist.” If only I could sing on key, I would have broken out into song.

Austin Winsbergis not only the creator and an executive producer of “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist,” but also, as a film writer, Winsberg penned the upcoming “Baby Nurse” (starring Leslie Jones), which is currently in development. On the TV side, Winsberg adapted NBC’s hugely successful live “The Sound of Music” event starring Carrie Underwood. His other credits include “9JKL,” “Gossip Girl,” “Jake in Progress,” “Wedding Album,” “Still Standing” and “Glory Days.” He has written numerous pilots for ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, Showtime, Amazon, Apple and Freeform, as well as movies for New Line, Dreamworks Animation and Warner Bros.

Winsberg is the book writer of the Broadway musical “First Date,” which enjoyed a sold-out run at Seattle’s 5th Ave/ACT Theatres prior to opening at the Longacre Theatre on Broadway in 2013. That show was licensed by Rodgers and Hammerstein and is currently playing around the U.S. and throughout the world. Winsberg graduated with a theater arts degree from Brown University. He is a five-time winner of the Blank Theater Company’s Annual Young Playwright’s Festival in Los Angeles. He continues to work actively with the Blank, directing and mentoring plays by teenage playwrights from all around the country.

About “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist”

Created by Austin Winsberg, the show follows Zoey Clarke (Jane Levy), a whip-smart computer coder forging her way in San Francisco. After an unusual event, Zoey suddenly starts to hear the innermost wants, thoughts and desires of the people around her – her family, co-workers and complete strangers – through popular songs. Based on Austin’s personal experience with his own father who passed away from a rare neurological disease (Progressive Supranuclear Palsy), he created a world in”Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist”where song could be used in lieu of speaking.

Susan Kouguell: Let’s start with your interesting career trajectory.

Austin Winsberg: My career started when I was 23. I’m from Los Angeles and after college I worked at New Line. I spent a year in development where I made a lot of connections with agents and managers because my boss had lots of scripts coming in. Then, I convinced Adam Goldberg to partner up. I met Adam (“The Goldbergs” creator) at Stagedoor Manor – who is a child prodigy playwright; he had written 70 or 80 different plays and I started reading them and then I started writing plays, which won five awards.

After a year working at New Line, Adam and I became writing partners, and we got staffed on “Glory Days”; Kevin Williamson created the show. We then wrote on “Still Standing,” and between that first and second year I created the concept of “Jake in Progress” which ran for two seasons. I went from being story editor to co-showrunner on that series at age 26-27. It was trial by fire.

After that my career had been writing pilots and on occasion writing for “Gossip Girl,” “9JKL,” and also “Sound of Music Live.” I sold a lot of movies, a good portion of that time had been spent selling a lot that hadn’t been made. I would sell big network pilots and they would never make it to the one-yard mark. It was the definition of insanity. Miraculously “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” came along.

Kouguell: How did you make the transition from theater to television?

Winsberg: I was a theater major in college. I made it from theater to television and back to theater again. The transition back to theater came out of pilots I had written that hadn’t been made. So much of what I like to do is collaborating with actors. I have two friends who are songwriters and we thought we should write a musical with the intent of putting it on Theatre Row. It was a seven-person musical, “First Date.” We did one 29-hour workshop, we got producers who wanted to do it and then it was produced in Seattle and then Broadway.

“Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” Writers’ Room

Kouguell: How do you collaborate in the writers’ room?

Winsberg: In season one, when we were in the actual room itself, we would break up all the stories in the room together. We had big white boards with character arcs, songs we wanted to use and different song ideas, and another board with each character, and included if they were singing one or more songs.

The musical element is a whole other narrative piece of each episode. As we are coming up with a song to include, we also talk about how choreography and dance numbers will work in the episode.

Now that we started writing season two, we are doing it on Zoom and still using white boards. It’s changing the way things get done; not everyone is in the same space.

The show features big, bold musical numbers from a catalog of hit songs. Every musical moment serves a purpose to reveal characters’ inner thoughts and feelings.

Kouguell: Do you and the writers ever create a show around a song?

Winsberg: It’s chicken and the egg. We write on the big white board the character and story arc discussions. For example: in Episode 5, when Simon comes over to Zoey’s apartment, we thought the song “Should I Stay or Should I Go” would be a great song for this character. It touched on certain points that we knew we wanted to build upon.

Usually it comes more organically from building the story first, and then finding the song that goes with it. I have strict rules about it: The songs need to advance the plot, the character, or be funny. We stay true to that.

Kouguell: How does it work with getting the rights to the music? Do you come up with a list and then choose what you’re able to use?

Winsberg: Ourmusic supervisor, Jennifer Ross, who worked on “Empire” and “Smash” – is my partner in crime. The second we think of a song, she’ll reach out and quickly see if we can get it, sometimes by contacting the artist directly. There wasn’t a song we didn’t get. We have a music budget, and because we’re creating our own version of the song, there are two types of song rights, which affects the price of the song.

Adapting from True Stories

Kouguell: This show is inspired by your personal experience with your father’s illness. How do you find objectivity when writing and creating episodes?

Winsberg: Coming from a writer’s perspective – every season is based on something in my own family. Some examples: My dad really asked for lemonade, there was a period of time where he didn’t stop crying, and there were several caregivers.

I would take the essence of the story and what happened to him and apply it. I would ask myself, what are the ways to tell that story that are inspired by the memories and experience we had, and what is right for the story. There is a separation there; taking the essence of what happened with my family and how to dramatize it that feels right for the show.

I draw from my own experiences, as well as consider what makes a good story. Certain things I felt strongly about, and it felt authentic. It was also about being able to understand what happened, incorporate what was appropriate, and use creative license.

My most favorite things in the show have not been true to my own life. There are aspects of Maggie that are based on my mother that I created that felt true to her. It’s important to understand the creative separation and not being shut off to ideas in the writers’ room and use these ideas to enhance and enrich the show.

In the process of building the show, I try to compartmentalize. On set with Peter Gallagher, who plays the father, sometimes I couldn’t always compartmentalize. I felt we were being authentic to my father and there were moments where it would be therapeutic and moments it was really hard.

Developing a Tough Skin While Surviving the Whims of the Industry

Winsberg: I spent many years waiting for my first pilot to air. It is a journey; there is something about the whims of the industry.

For me, the ideas of perseverance and to keep writing were important because you never know which project is going to connect. Some of it is timing and luck. And hours of work. And a tough skin. I remember many times when I would read pilots that were bad and wonder why did they get picked up?! I would get depressed about it. I got better over the years to not personalize it so much. For me, it was important to work on several things at once.

Kouguell: Your closing thoughts about your journey thus far with “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist”?

Winsberg: What I could not anticipate was the emotional impact and the huge outpouring of texts and emails from people reaching out to me during and after the show who had the disease, or people who had lost loved ones (due to COVID), and shared their grief.

I didn’t expect this connectivity. Their stories are so emotional and personal. When I created “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist,” I just wanted to write something personal, and I found the more specific, the more universal it becomes.

Season 1 of “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” is currently streaming on NBCUniversal’s new streaming service Peacock, the NBC App and HULU. The show has recently been renewed for a second season.