I’ve always looked to explore genre where the female gaze has been historically excluded: Science fiction, horror, Westerns, and now film noir with this gift of a savage and subversive script capped with a dynamic female-driven twist.

Alice Troughton

In a wide-ranging discussion, I spoke with internationally acclaimed director Alice Troughton about her film The Lesson, which had its premiere at the 2023 Tribeca Film Festival. Troughton led, directed, and executive-produced Baghdad Central (2020) for C4, Troughton is also known for her work on the award-winning shows The Living and the Dead, Cucumber, Tin Star, A Discovery of Witches, and Doctor Who. In 2022 Troughton completed work on The Midwich Cuckoos for Sky.

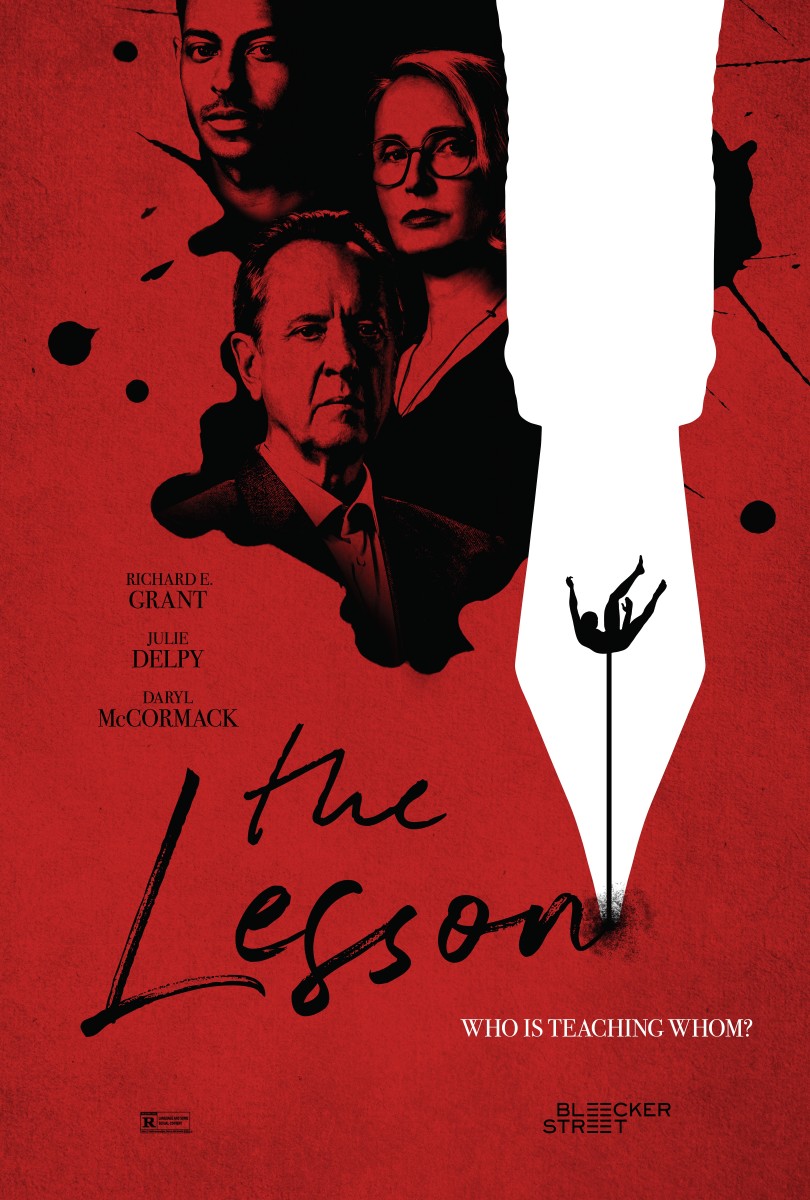

About The Lesson: Liam, an aspiring and ambitious young writer, eagerly accepts a tutoring position at the family estate of his idol, renowned author J.M. Sinclair. But soon, Liam realizes that he is ensnared in a web of family secrets, resentment, and retribution. Sinclair, his wife Hélène, and their son Bertie all guard a dark past, one that threatens Liam’s future as well as their own.

![[L-R] Richard E. Grant as J.M. Sinclair, Daryl McCormack as Liam Sommers, Julie Delpy as Hélène Sinclair, and Stephen McMillan as Bertie Sinclair in Bleecker Street's THE LESSON. Photo by Anna Patarakina, Courtesy of Bleecker Street.](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MTk5MTY4ODY4ODgxNTQxMDA3/thelesson-anna-patarakina-courtesy-of-bleecker-street.png)

KOUGUELL: You worked closely with producer Camille Gatin and screenwriter Alex MacKeith, as you stated, “to mine the dark corners and sultriness of the script which felt full of urgent questions: What do we do with art of monstrous men? How culpable are all parties involved in coercive control? Can we reclaim the film’s narrative from the traditional patriarchal noir archetypes? How does anyone navigate and survive the British class system?”

TROUGHTON: We didn’t want to be didactic. I’m not at all afraid of going on a polemic, but I think it’s necessary sometimes. I also think there’s always a way of catching flies with honey, making sure that the second-class status of women in the industry and in the whole world – and that includes women and women-identifying – that there is an inclusive feminism of mine; there’s nothing more important in my filmmaking than that.

KOUGUELL: This is the first feature film that you directed. Let’s talk about the transition from television to film.

TROUGHTON: First of all, I was very lucky as it was my first film experience. We all had toxic jobs and this wasn’t one. I feel that I was picked in turn by producers who wanted my vision. It all came from a show that I directed that won huge amounts of awards called Cucumber, which was by Russel T Davies, one of our finest writers.

There’s an affinity between my gaze and his; it’s just not the female gaze. We collaborated a lot of times; he’s the showrunner on Doctor Who. That experience allowed me to be free in my filmmaking, which is what my producers gave me on The Lesson. Obviously, Alex wrote this page-turner of a script. A lot of it is semi-autobiographical so it came from the heart. He’s also a complete wordsmith; his writing has his own style of acerbic wit and he’s a stand-up comic.

KOUGUELL: The Lesson is a contemporary noir that challenges the traditional definition of this genre.

TROUGHTON: We tried to subvert those norms. I think you can watch the film and have no idea about the noir archetypes. I wanted it to be just that fantastic Witness for the Prosecution rapport that you enjoy at the end of a good thriller. There’s also a meta-level of it, which you’re also subverting the traditional noir roles. If you are a noir fan and a noir filmmaker – there’s the femme fatale, the detective, the monster – those strong archetypes. We wanted to have fun with that.

KOUGUELL: Hélène’s character arc is quite an engaging slow burn.

TROUGHTON: Hélène is kind of mute. She’s not only mute around the dinner table, she’s mute in the way that the femme fatales were mute. She’s the object of desire; she’s identified through the gaze of other people, which is something obviously you’re getting into the semiotics of the gaze, something that is very noir identifying.

There is a really key and subtle moment, which is the moment that she breaks the gaze from being objectified, to returning Liam’s gaze and she looks straight at him. It is the moment that you realize that Hélène’s role is changing and that leads you to the moment to the end. She in fact is the detective. She isn’t the femme fatale. She’s playing the detective role and that always has been her role from the start.

![[L-R] Julie Delpy as Hélène Sinclair and Daryl McCormack as Liam Sommers in Bleecker Street's THE LESSON. Photo by Gordon Timpen, Courtesy of Bleecker Street.](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MTk5MTY4OTk5ODc4MDQzNTM1/thelesson-gordon-timpen-courtesy-of-bleecker-street.png)

KOUGUELL: Tell me about the shoot.

TROUGHTON: We had 22 days of shooting. It was a low budget. We needed efficiency. There was such a sense of play on that floor and joy, we all were exactly where we wanted to be to do that. There was extraordinary chemistry.

KOUGUELL: The music by Isobel Waller-Bridge was incredible and added an important layer of conflict that was referenced in the narrative.

TROUGHTON: I had heard her work on Emma and Fleabag, and when I met her we platonically fell in love. She was with the project from the very start, it was five years from the inception to the film getting made. What she’s done in the film is astonishing, it’s hugely dramatic and at the same time very subtle. The music is gorgeous and gives the film a vivacity. We were talking a lot about Russian composers like Rachmaninov, Borodin, and Tchaikovsky; they have circus and pomp and ceremony. They were great as influences.

KOUGUELL: There are other influences as well. You looked at the history of artist couples —Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes – in which the male spouses and their notorious egos, garnered attention.

TROUGHTON: We looked at objectification, sexual politics, and the denigration of women in the arts to redress that balance.

KOUGUELL: The objectification of women on screen brings to mind Nina Menkes’s documentary Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power. The character of Hélène is watching the men and she was the one in power; she has agency.

TROUGHTON: Yes, and Hélène breaks that gaze. I watched Menkes’s film after I made The Lesson. In Brainwashed, Menkes quotes Agnes Varda: “The first feminist gesture is to say: “OK, they’re looking at me. But I’m looking at them.” The act of deciding to look, of deciding that the world is not defined by how people see me, but how I see them.”

There’s a point when we break the gaze of objectification. It is scored, but it is not scored as a big moment; it’s scored when Hélène returns the gaze, and that changes her from being objectified into the person who is doing the looking. Varda’s “I will look back at you” – that is exactly what Hélène is doing. That made me very happy when I heard that quote afterwards. It is about Hélène going: I can change the view, I can reclaim the gaze.

KOUGUELL: The theme of redemption is at the heart of The Lesson.

TROUGHTON: For me as a filmmaker, it is a particular interest of mine. I believe in redemption and I believe in a redemptive ending, and in an Aristotelian way of saying that drama is inspirational and cathartic and that you can also be inspired by redemptive endings. I like an ending with morality.