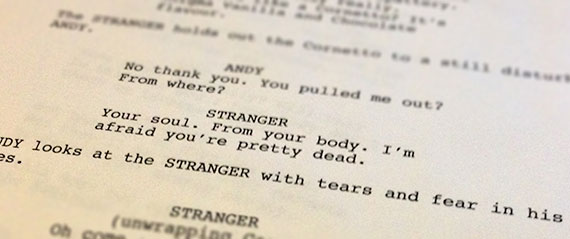

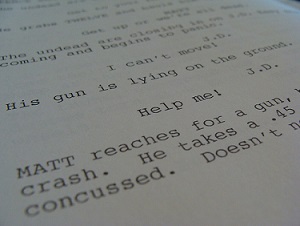

Readers must have a clear understanding of who your characters are and the reasons why they take the actions they do in your screenplay; otherwise your script will be rejected.

Successful characters are multi-dimensional with distinctive physical attributes, emotional traits, appearances, personalities, intelligence, vulnerabilities, emotions, attitudes, idiosyncrasies, a sense of humor or prevailing despair, secrets, and hopes and dreams. Writing solid and memorable characters also means digging deep into their past and present.

There are several ways in which to delve into characters, such as writing character bios in the character’s voice. (I offer various templates and examples in my book Savvy Characters Sell Screenplays!). Use whichever exercise works best for you. The bottom line is that you must know your characters inside and out.

The 14 Vital Points to Address in Your Character Outline

The following points to address for each of your main characters and for your significant supporting characters:

1. Character Arcs: How do my characters evolve in the beginning, middle, and end of the script, as they attempt to achieve their goals?

2. Journeys: What do my characters learn about themselves and others, and what do my characters gain or lose, as the plot unfolds?

3. Multi-dimensional: What are my characters specific emotional, mental, physical, and/or social behaviors and traits? How do my characters see themselves and how do they relate to others?

4. Empathy: What elements make my characters likeable and unlikable?

5. Goals: What are my characters main goals and why are these goals important? How do my characters plan to achieve these goals?

To read more:

http://thescriptlab.com/features/screenwriting-101/2773-the-14-vital-points-for-outlining-characters