Agnieszka Holland discusses the inspiration behind the film, her collaboration with screenwriters Maciej Pisuk and Gabriela Lazarkiewicz, the creative decision behind filming in black and white, and more.

I had the pleasure to speak with Polish director and writer Agnieszka Holland about her latest feature film Green Border. A three-time Academy Award nominee (Angry Harvest, Europa Europa, and In Darkness), Holland, in addition to her numerous award-winning features, has also directed episodes of many notable television series, including Treme and House of Cards.

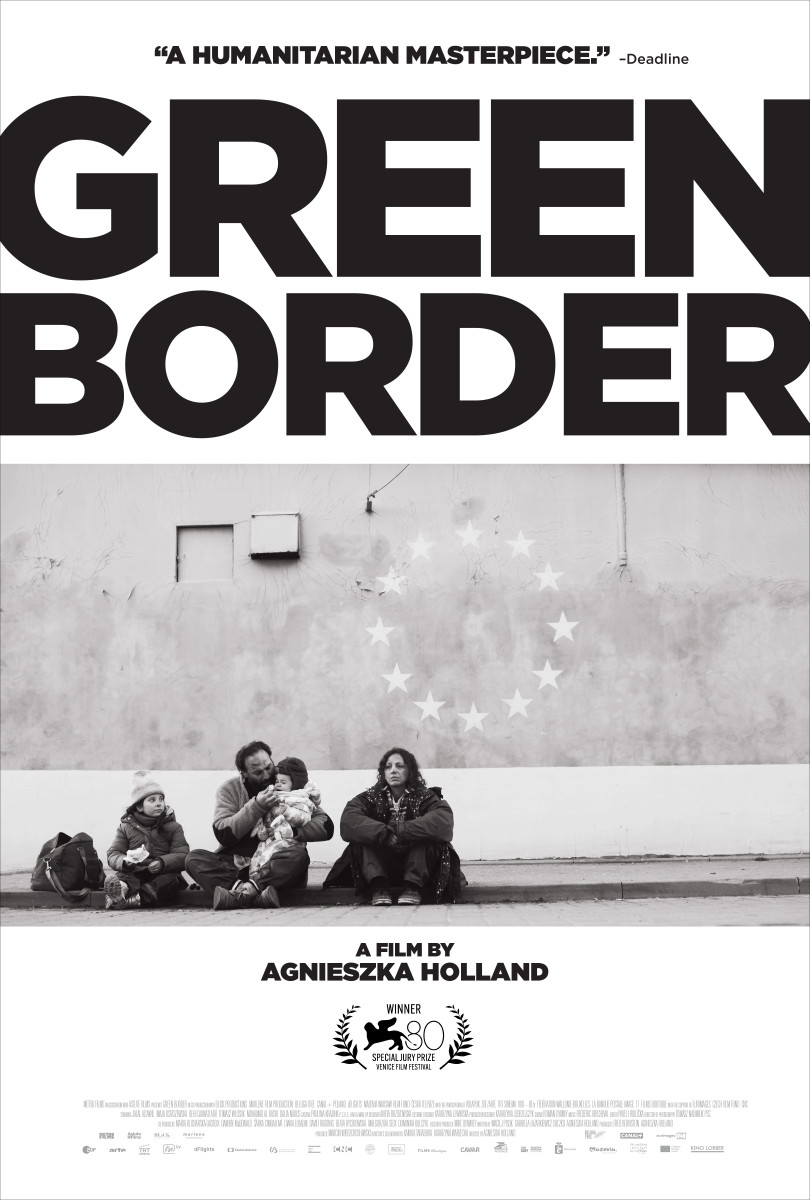

About Green Border

In the treacherous and swampy forests that make up the so-called “green border” between Belarus and Poland, refugees from the Middle East and Africa are lured by government propaganda, promising easy passage to the European Union. Unable to cross into Europe and unable to turn back, they find themselves trapped in a rapidly escalating geopolitical stand-off.

Winner of many international awards, including the Special Jury Prize at the 2023 Venice Film Festival, Green Border underscores the themes of ‘there are two sides to every story’ and the moral choices characters must face.

Kouguell: What was your initial inspiration for the film?

Holland: Reality was the inspiration. I made several films about the Holocaust, and Mr. Jones, about the crimes of Stalin and a Welsh journalist no one wants to listen to. In 2015, during the big crisis of refugees from Syria coming to Europe, people were afraid of the newcomers from those countries. It was easy to manipulate those fears with dictators like Putin, and the local extreme right and nationalistic movements. That’s why I wanted to tell that story, to humanize those who have been dehumanized by the propaganda and give them voices and faces.

Kouguell: The screenplay centers on three very different perspectives and viewpoints; the Syrian refugee family, a young border guard, and a middle-aged female activist. Tell me about your collaboration with your co-writers Maciej Pisuk and Gabriela Lazarkiewicz.

Holland: The film is based on real facts. I decided to try to make the film a few weeks after the crisis on the Polish border started. First, I did extensive research with everybody who knew something about the crisis or who was living through it and had a distinct point of view. I contacted two friends, one an experienced screenwriter who happened to be an activist and knew a lot of activists who were working on that border. And the second (screenwriter) was a young woman, who was pregnant when we were writing it and her sensibility was very important. Her husband is a doctor, an anesthesiologist, and he created a group of volunteers who went to the border and tried to help, and saved several lives.

My co-writers had experiences about the border, about the situation, about the logic of the activists and refugees. I talked to activists and refugees and collected recordings of conversations with them. At the beginning we thought people would be too afraid to talk to us, but by the end, even the border guards contacted us. It was important because it confirmed what the other side was saying and it confirmed the psychological aspects of what they were going through.

Then we had to decide our approach. We had two different opposite concepts; one was to find the moment, place and person and focus on that, or make it more epic and give multiple points of view. I decided to go for the second because I knew how much the migration crisis is present now for years although it’s not very well known. I wanted to show the complexity of the situation and show it through different eyes and different perspectives.

Kouguell: How did you structure the interweaving of these narratives?

Holland: We divided the storylines and everyone wrote their storylines based on their experience and research. After that we put it together, correcting and improving each other’s story and deciding on how they will be told in all, to find the emotional moments and the dramaturgy.

Kouguell: The film is shot in a quasi-documentary style.

Holland: We wanted that immediacy of that style and the camera in motion. In fact, it was impossible to shoot in a different way because we had such a short time and so many scenes and so many actions. I was very in sync with my cinematographer, and also the two women who were shooting the parallel units. There was a lot of footage, and after that, a lot of things were decided upon in the editing room.

Kouguell: Why did you choose to film in black and white?

Holland: I wanted a metaphorical quality and timelessness. You see the cell phones but at the same time it could be 1942. For the local people, a lot of imagery was striking especially in that area because of the tragic situations that took place there. During the Holocaust, it was close to the death camp where there was the uprising of the prisoners who were hiding in the same forest. There are a lot of hidden memories in that forest. To see these similar images in the film shows that it can come back.

Kouguell: The film received strong criticism from Polish politicians. Your reaction?

Holland: I expected it to some extent but I didn’t expect the hate campaign would come from the highest authorities and it would be so violent. Somehow it helped for the publicity of the film. People were very curious and went massively to see the film in Poland.

The new government is practically doing the same things and pushing the nationalist fear and the fear and hate of others. They’re using the migration crisis for their own means. I’m pessimistic about that but I’m very glad that we made the film and it is very important to many people.

Kouguell: Final thoughts?

Holland: At a Q & A after the film was shown in France, one young woman asked me if the film can change the world. I said, ‘No, I don’t think so, the world is too deeply in trouble.’ The woman said, ‘Maybe you didn’t change the world but you changed my world.’ That is the biggest satisfaction I can have.

Green Border opens in theaters in New York on June 21, 2024 at the Film Forum and on June 28, 2024 in Los Angeles at Laemmle Royal.