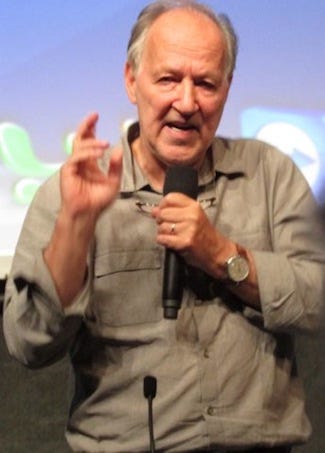

Master Class with Werner Herzog at the Locarno Film Festival

German director, screenwriter, producer and actor Werner Herzog was awarded the Pardo d’onore Swisscom at the Locarno Film Festival on the Piazza Grande on 16 August. In addition to the screenings of his films during the Festival, Herzog conducted a Master Class hosted by Grazia Paganelli, author of Sinais de Vida: Werner Herzog e o Cinema .

The intensive Master Class covered a wide range of topics — from shooting on celluloid versus digitally — to the challenges of working in fiction and documentaries — to recounting compelling and often humorous anecdotes, including his voiceover acting role on the animated series The Simpsons.

German director, screenwriter, producer and actor Werner Herzog was awarded the Pardo d’onore Swisscom at the Locarno Film Festival on the Piazza Grande on 16 August. In addition to the screenings of his films during the Festival, Herzog conducted a Master Class hosted by Grazia Paganelli, author of Sinais de Vida: Werner Herzog e o Cinema.

The intensive Master Class covered a wide range of topics — from shooting on celluloid versus digitally — to the challenges of working in fiction and documentaries — to recounting compelling and often humorous anecdotes, including his voiceover acting role on the animated series The Simpsons.

Herzog detailed his vast experiences, offering insight and strong opinions about both fiction and documentary filmmaking. Showing clips of his films, as well as a clip from the opening of Viva Zapata, “Just to see how ingenious you can be to introduce your characters; I’ve never seen a better introduction of any film,” Herzog addressed the importance of casting a documentary, similar to that of a fiction film.

The conventions of documentary filmmaking is a topic that Herzog is quite passionate about, as seen in his films and as discussed throughout the Master Class, raising questions about staging situations and scenes, shooting retakes, and selecting (casting) the characters.

What is the truth in the documentary narrative? Is it subjective — satisfying the director’s vision and intent? Does objectivity occur when

something unexpected occurs in front of the camera?

Advice

- It’s a very dangerous thing to have a video village, a video output. Avoid it. Shut it down. Throw it into the next river. You have an actor, and people that close all staring at the monitor gives a false feeling; that ‘feel good’ feeling of security. It’s always misleading. You have to avoid it.

- I always do the slate board; I want to be the last one from the actors on one side and the technical apparatus on the other side. I’m the last one and then things roll. You don’t have to be a dictator.

- Never show anyone in a documentary, rushes. They’ll become self-conscious. Never ever do that.

- Sometimes it’s good to leave your character alone so no one can predict what is going to happen next. Sometimes these moments are very telling and moving.

- Dismiss the culture of complaint you hear everywhere.

- You should always try to find a way deep into someone.

From One Second to the Next

“There are millions who have cell phones; everyone can make films and photos on phones. The Internet is spread out into everywhere so you have to find your own means; new outlets for distribution. I’m just in the middle of discovering it. I just made a film From One Second to the Next released a few days ago. It’s new terrain; you have to be daring enough to test it.

From One Second to the Next, a documentary about texting and driving — there were 1.7 million viewers in a few days. It functions because you have to offer something that has great

substance. It doesn’t matter whether you distribute it in theaters or DVD; you need to articulate something no one else has. Stick to your own vision. Be bold enough to follow your vision. You have to earn $10,000 and make a feature film. I would never accept any complaint from anyone.”

Find Your Voice

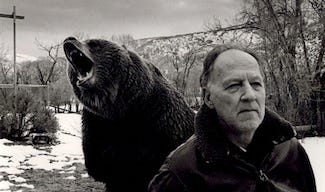

“It took me quite a while until I found my own voice, my cinema voice. I found it through a long process in documentaries, notably in Grizzly Man, and Cave of Forgotten Dreams. You have to find your own voice; it’s not a physical voice. It’s something you can get across on the screen. The caliber of a person is always visible on screen.”

Taking Control of the Set

“Filmmaking itself, I don’t spend much time. I do the essentials and everyone is nervous on the film set. Like on The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call — New Orleans. I was asked: ‘Why don’t you shoot coverage?’ I took my assistant aside and asked, ‘What do they mean by coverage? I have coverage for my car, $250,000 for bodily damage.’ I shoot what I need for the screen. The second day when everyone was complaining

about coverage, Nicholas Cage said: ‘Silence. Can I say something?” He said to everyone, ‘Finally someone who knows what he’s doing.’ I felt very proud of that. It somehow silenced the kind of fear. There is always fear on a set.

You have to take control of your set. Whatever you do. Where ever the camera is, even if it’s not rolling. I have no walkie-talkies within 30 meters of the camera. No cell phones within 100 meters away from wherever the camera is located. All of sudden you have focused sets.”

On Grizzly Man

“Intimacy and power. It’s an essential quality of filmmaking. Set ethical boundaries before shooting. The story behind Grizzly Man was known to the general public about Timothy and his girlfriend eaten by a bear. There was only the audio because the attack was so violent. Apparently the girlfriend switched on the camera. They had no time to take off the lens. The camera was found inside the tent. Everyone insisted I had to show it. Everyone wanted me to address it. There is a dignity that must not be touched. It’s the privacy of death.”

Anti-Film School

“You should gain experience in life and I would advise everyone don’t spend time in film school. If you travel by foot for four months, it’s better than four years in film school. Read. Read. It gives you different perspectives. You enter in a different way. Doing essential things like raising children, those who have done it are normally better grounded in reality. Otherwise it’s not going to function.”

The Controversy of Staging a Documentary

“Long ago at a festival where I was on a panel, they were raving about Cinéma vérité. A young woman was exuberant, saying that one had to be a fly on the wall. I thought, ‘Oh my God I can’t take it any longer,’ and grabbed the microphone and said, ‘No one should be the flies on the wall. We’re the hornets that have to sting.’ You’re not the security camera in the bank with video running for two and a half hours, waiting for that someone who steals money.”

The Parallel Story

“There is one thing you have to be very careful about in both documentaries and feature films — there is a special parallel story that occurs with the audience. The audience anticipates and rushes ahead of your story. For example, in a romantic comedy, there is a story evolving in the collective, ‘I hope they kiss each other.’ If you don’t understand the parallel story you will never make a great film. Pay attention to what you are seeing in cinemas; to what you see evolving on the screen.”

Silence

“Trust your cameraman. Never whisper. Never stir. Just stand there. It is unusual. The network for example, says the movie has to go ‘fast’ and ‘cut this whole thing out.’ And I say no, ‘If I cut this silence out, I have lived in vain.”

Undoubtedly, Werner Herzog will continue to challenge film studios, his audience, and narrative conventions both in his fiction and documentary films.