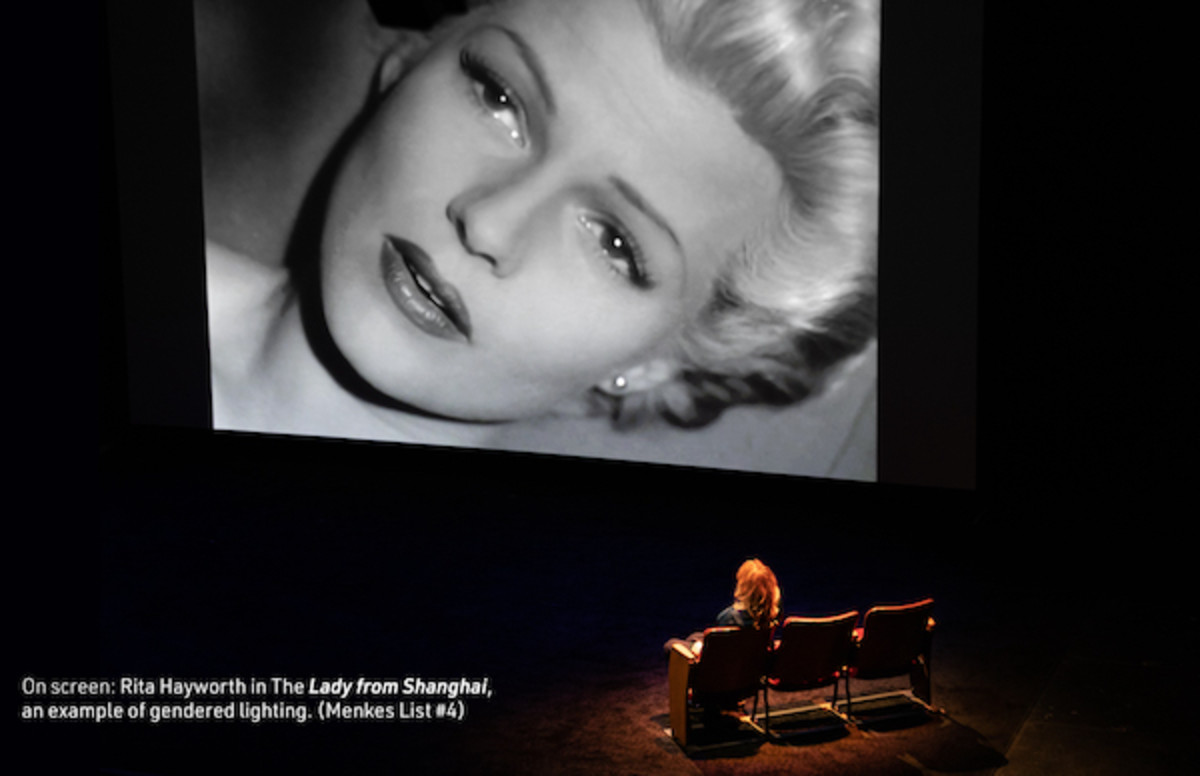

Filmmaker Nina Menkes discusses her thought-provoking and illuminating documentary ‘Brainwashed: Sex- Camera-Power,’ which explores the sexual politics of cinematic shot design, showing how this visual language of cinema connects to both severe employment discrimination against women – especially in the film industry – as well as to the epidemic of sexual harassment and abuse that was exposed through the #MeToo movement.

Considered a cinematic feminist pioneer and one of America’s foremost independent filmmakers, Nina Menkes has shown widely in major international film festivals and museums. Honors include a Los Angeles Film Critics Association Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, an AFI Independent Filmmaker Award, a Creative Capital Award and an International Critics Award (FIPRESCI Prize).Menkes holds an MFA in Film Production from UCLA , is a directing member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and is a member of the faculty at California Institute of the Arts.

In our wide-ranging and eye-opening conversation over Zoom, Menkes and I discussed her thought-provoking and illuminating documentary Brainwashed: Sex- Camera-Power, which explores the sexual politics of cinematic shot design, showing how this visual language of cinema connects to both severe employment discrimination against women – especially in the film industry – as well as to the epidemic of sexual harassment and abuse that was exposed through the #MeToo movement.

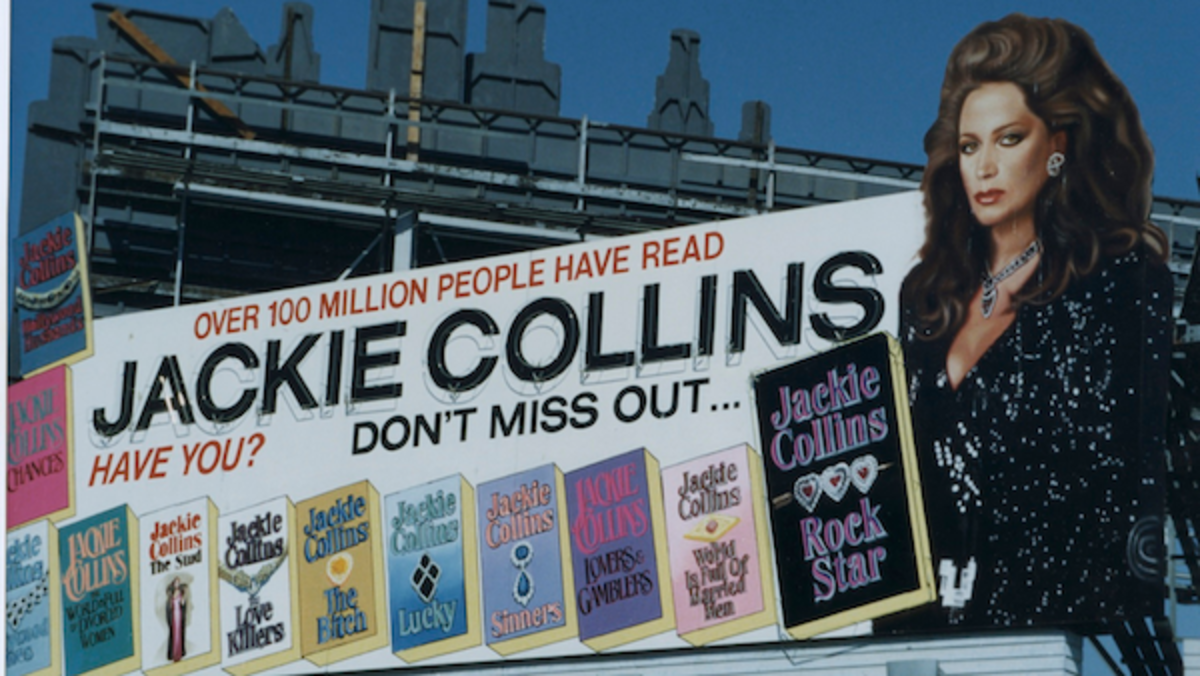

This social issue documentary uses over 200 film clips from 1896 through the present and includes 23 interviews with women and non-binary industry professionals, including Julie Dash, Penelope Spheeris, Charlyne Yi, Joey Soloway, Catherine Hardwicke, Eliza Hittman, Rosanna Arquette, and Laura Mulvey.

This must-see film should be included in the curriculum for all filmmaking, screenwriting, and cinema studies students.

KOUGUELL: Let’s start with your personal background. Your mother’s parents were German Jews who fled Hitler’s genocide, settling in Jerusalem in 1933 and your father’s Austrian Jewish family perished in the concentration camps. This type of trauma, particularly for you as a first-generation American, forever remains. How does your specific background of family trauma and the violence of objectification inform your work?

MENKES: I’m so glad that you brought this up, no one else has brought it up. I happen to think it’s really key. My mother was a baby in 1933, and her parents got out of Berlin and she was raised in Jerusalem. My father’s whole family were all gassed to death. My father was taken as a child, in a secret rescue to Jerusalem in 1940. My parents got married there and later immigrated to the United States.

This experience obviously impacted my family. The fact is that they [researchers] found that trauma is transmitted via DNA, I grew up with the idea that systems of power can be corrupt, and systems of power that are supported by the majority does not mean they are right.

I grew up in a household that rejected the idea that popularity is a sign of moral greatness on a very deep level. A second important point to this, the Jews before they were murdered in the Holocaust, were objectified by the Nazis. You cannot treat another person in the way that the Jews were treated in the concentration camps if you think of them as full-on human subjects. You have to denigrate them in your own mind before you can even do these actions; this has all been extensively documented.

I’m not trying to make an equivalency between what happened in the concentration camps and sexist representation in film, there’s a big gap there. There is a certain level of intersection with the idea that objectification is not a beautiful thing, and objectification is tied to violence. Extensive research has shown that women who either consume objectifying media or self-objectify as it’s done on Instagram, every minute of the day, has been correlated to body dysmorphia, eating disorders, and higher levels of shame than those who don’t do it, and a higher acceptance of sexual harassment, and even sexual assault. This whole thing of objectification is not just fun and games.

KOUGUELL: Brainwashed stemmed from your lecture presentation “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression” which was at Sundance’s Black House in January 2018, for the launch of Gwen Wynne’s Eos World Fund. Tell me more about this and how it turned into this film.

MENKES: There are a lot of differences between the two. The lecture had 10 film clips and this film has 200, and millions of other differences. The idea was, how can we bring some of these concepts that some people in the PhD film theory world discuss, to film watchers who are not exposed to those ideas?

For those people who know my other work, it tends to be slightly towards the art film and avant-garde film direction. I certainly never thought about the audience when I made my own feature films. This documentary was about how can we prove our case and have the film be fascinating and interesting for sophisticated filmgoers, as well as some person who is not focusing on film as a profession, but a film watcher, which is kind of everybody.

That was challenging, and based on reactions, some people seem to love it. We’ve shown it in all the major film festivals and have gotten some amazing reviews, and we’ve also been attacked, and interestingly we’ve mainly been attacked by other women. People are very invested in their feelings about cinematic masterpieces.

KOUGUELL: Would you say that this lecture served as your script and/or outline for this documentary?

MENKES: The lecture is the core thing that we jumped off of but making the film I worked closely with the editor and creative producer, Cecily Rhett. In fact, I’ve been telling imdb.com to take my name down as writer. I don’t really claim to be the writer, but in a documentary film, the editor is in many ways the writer of the film. I was there for every second of the journey and participated in the decisions. There was no bona fide script as with most documentaries. Cecily had an amazing program called Dynalist, which we used to organize and structure our ideas. It was very collaborative.

KOUGUELL: In your own experimental narrative films, you worked with a small crew. How did that change, if at all, when working on this documentary?

MENKES: It seems like a bigger crew when you look at the credits, but each shoot didn’t have that many people. The overall project was more elaborative, in terms of making my narrative films, which I write, produce, edit, and direct.

This film was more complicated on so many levels. Regarding editing, I needed a pro editor who understood the deep issues that I am laying down here and knows me and my work and has background in commercial narrative and documentary film. I was lucky to get Cecily Rhett who had all those qualifications, I’ve known her for a long time, it was a very collaborative process.

There were a lot of people involved in the film research, and then there was the legal part, you have to clear every single clip through attorneys. There was a lot of attorney interaction and the attorney actually influenced a lot of our decisions, because he would say, ‘This clip won’t fly for fair use, you have to find another clip.’ Or he would say, ‘You need to include voice over because it won’t fly for fair use.’

The postproduction was complex, with all these film clips. There was no time code; every single picture and sound was hand matched by Jim Rosenthal, our brilliant postproduction producer.

With the score, I never worked with a composer before. It was challenging for me because I always did the sound myself on my films. Composer Sharon Farber did a genius job.

All those things made it a bigger production. A lot of the interviews were over Zoom because we were in the middle of the pandemic. For example, it was me on Zoom and a team in Atlanta when we interviewed Julie Dash.

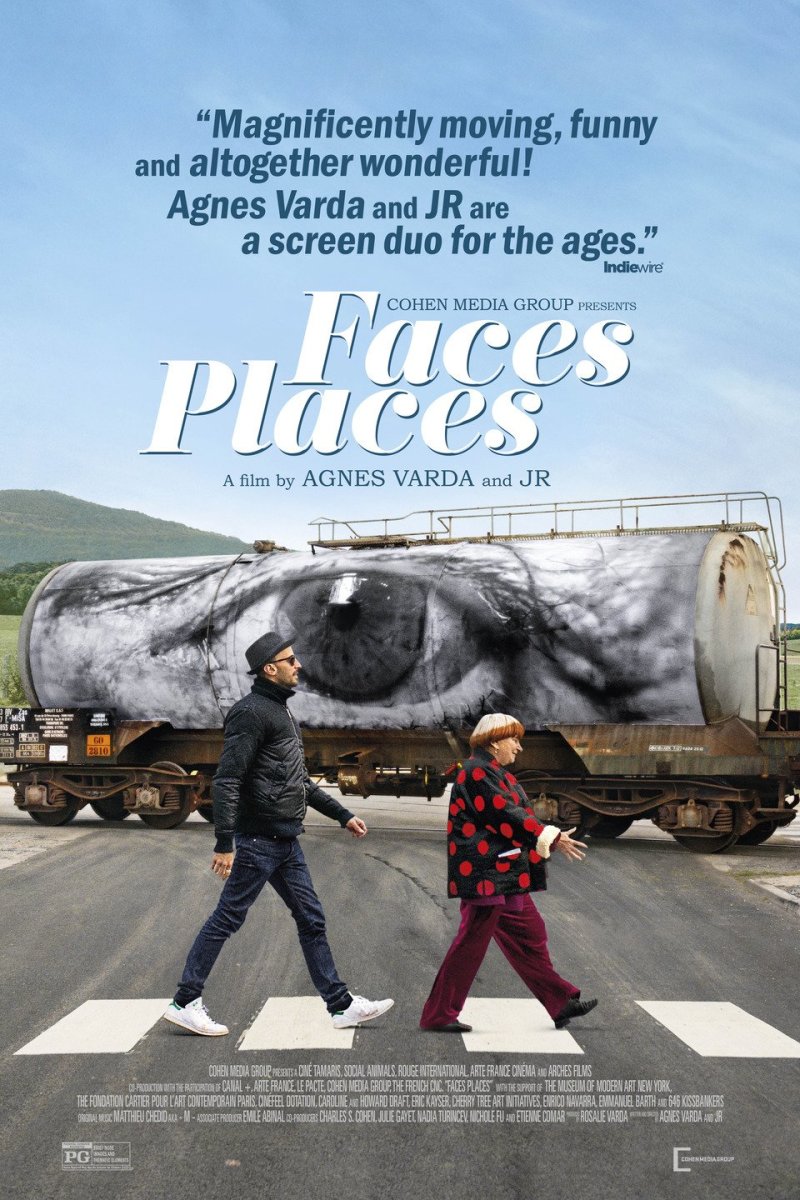

Kouguell: How did these films that you include in your documentary, such as Orlando, LeBonheur, Daughters of the Dust, and so on inform your own work?

Menkes: I was more reassured by seeing [Agnès Varda’s] Vagabond and [Chantal Akerman’s] Jeanne Dielman (which Menkes didn’t see until after making her film Magdalena Viraga) that there was someone else out there in the world who had similar feelings.

Kouguell: During production, the Brainwashed team reached out to representatives of almost all the living directors whose work is included in the movie, including Sofia Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott, Spike Lee, Quentin Tarantino, and Denis Villeneuve among many others, to invite them for on-camera interviews. They declined the opportunity to participate.

Since the completion of this film have you heard from any of them?

MENKES: No not yet – the film is coming out on Friday.

The film will open in New York City at DCTV downtown and in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Theaters Friday October 21st with a national rollout to follow.

Learn more about the film and rescources here.