SUSAN KOUGUELL for Script Magazine

Celina Murga discusses the scriptwriting process, the major themes of gender roles in the workplace and at home, and the conflicts and repercussions of the actions of the male and female professor in each of these environments.

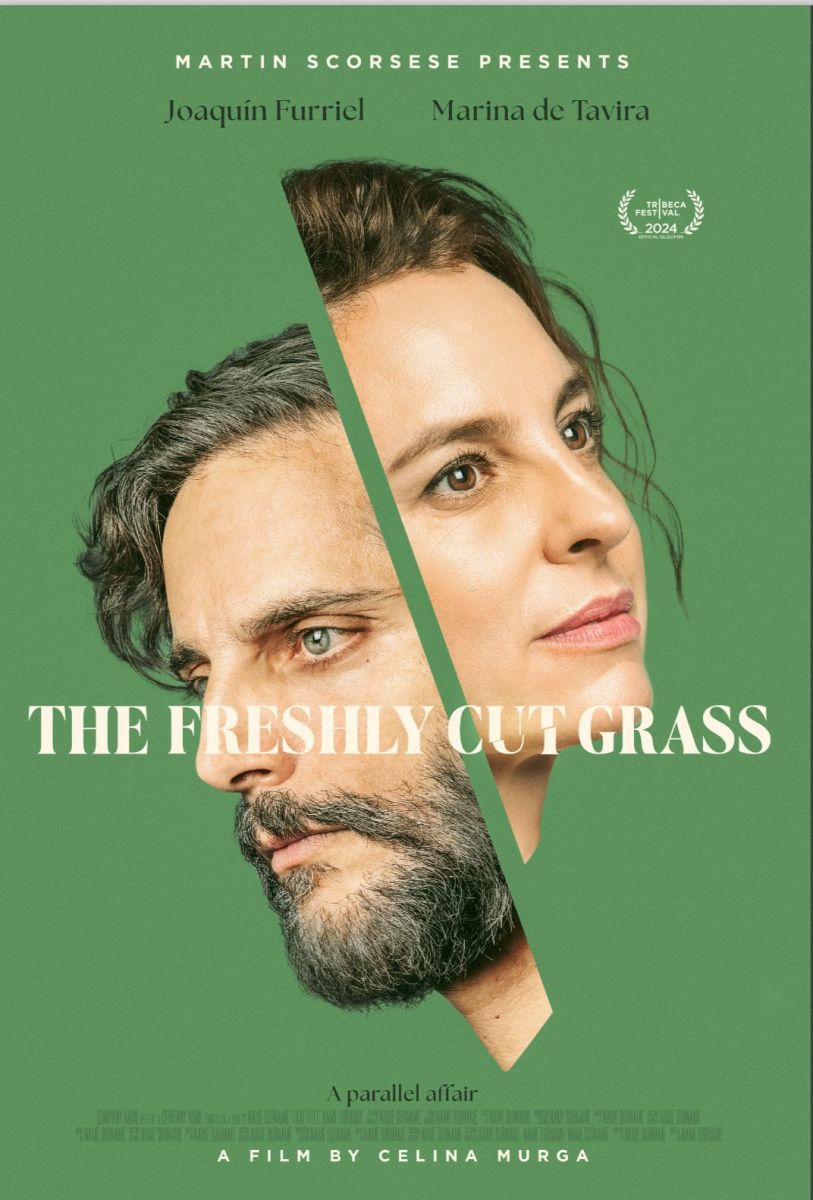

Premiering at the Tribeca Festival in the international narrative competition The Freshly Cut Grass directed by Celina Murga, and written by Murga, Juan Villegas, and Lucía Osorio, is executive produced by Martin Scorsese.

About the Film

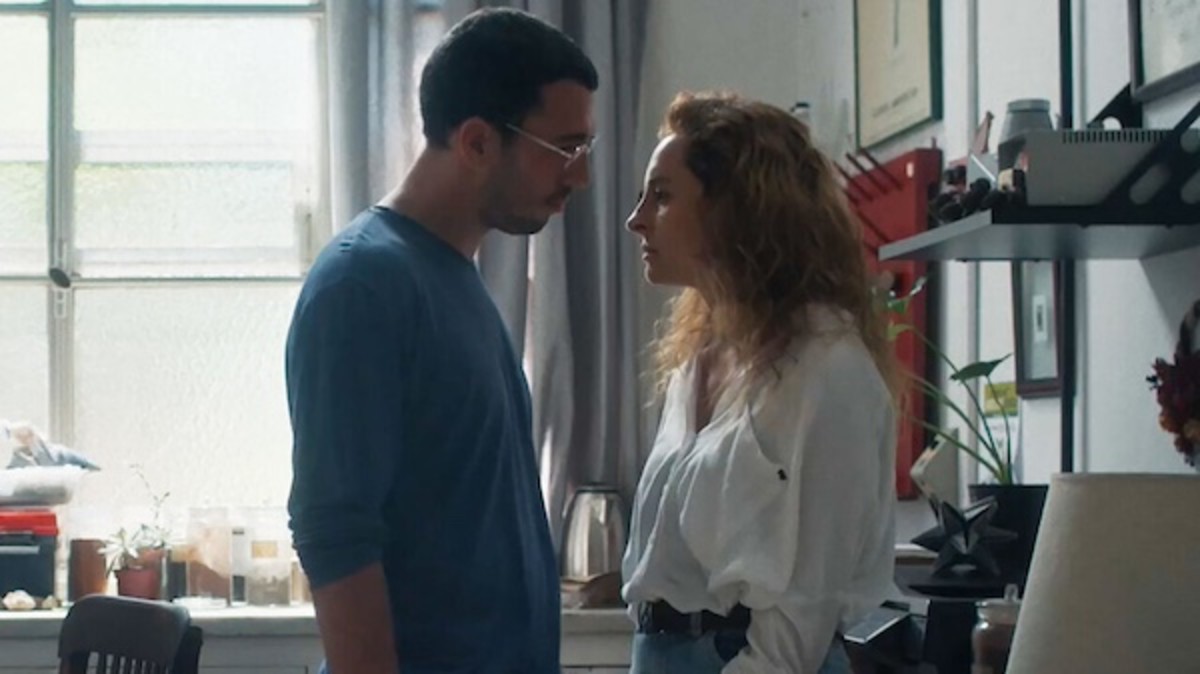

A male professor at a university is in conflict with his own roles as husband, father and teacher. The eventual relationship with a female student highlights his crisis. As in a mirror, a female professor, also in crisis, has an eventual relationship with a male student. The duplicate story questions the power relations between genders.

I had the pleasure to speak with Argentinian writer, director and producer Celina Murga during the Tribeca Festival about The Freshly Cut Grass. We discussed the scriptwriting process, and the major themes of gender roles in the workplace and at home, and the conflicts and repercussions of the actions of the male and female professor in each of these environments.

The parallel storylines are thought-provoking, and avoid cliche and predictability.

Kouguell: Let’s start with the evolution of Freshly Cut Grass from script to screen.

Celina Murga: It was a challenging process from the beginning because we knew that the possibilities of telling the two stories about human relationships are complex. It was challenging to mirror the stories.

We worked a lot with the actors. We shot first with Joaquín [Furriel] and then the Marina [de Tavira] story to mirror the story on a set. We worked hard to try to find a way to connect with their situations and to build these characters, knowing the complexities they are immersed in.

Kouguell: Tell me about your screenplay collaboration with your co-writers Juan Villegas, and Lucía Osorio.’

Celina Murga: I always like to be involved in the writing process and write stories I care about. I like to work with others who give their point of view to what I’m doing. It’s a very democratic process. Sometimes in the beginning, Juan and I wrote one character, I wrote about Natalie and he wrote about Pablo and then we switched characters.

We were going to shoot in 2020 but then there was the pandemic. During this time we kept reflecting about the story and characters. We showed the script to others we trusted because it was important to figure out if the situations were subtle enough.

Kouguell: In his executive producer role, what input did Martin Scorsese have on your film?

Celina Murga: He allowed us to reach more producers. In a more creative way, he read the first version and saw one of the first edited versions. He was part of the creative process, and very supportive and generous with me. He’s someone who likes to be there and be part of it, and at the same time aware of me as a woman director and not someone to push the story he wants to tell on me. In that deeply profound way, he is a true mentor in allowing me to find my own voice.

Kouguell: You mentioned that the story developed from two characters in crisis, and that this idea proposed a very particular structure that restricts and provokes certain ideas of mise en scène, and aims to be a mirror in which two very similar stories take place. How did you develop the script’s structure?

Celina Murga: When we started writing this film in 2018, in Argentina we were in a big movement regarding families and we were talking about these ideas of how men and women are sometimes different and many times are also equal.

In the story we wrote, we knew that these two characters were going to be in a middle-age crisis and in a particular moment in their lives, asking about themselves as fathers, mothers and teachers. An important part of the process was to find the scenes where they were similar and at the same time not literally similar, and that was a really beautiful process to find a way that each character has their own particularities.

It happened in the script but also in the editing room process; the editing room is another way of rewriting the script and it’s very important.

Kouguell: Although the film is set in Argentina, the story feels universal.

Celina Murga: Argentina is where I was born and my home, a place where I know and am interested in talking about human behaviors. And it is very universal. For me, the film is about how we relate to each other and what it is to be a family, and what it is to be in a marriage of many years. It also questions how society and culture have made us a part of these systems. My main goal is to find more honest ways of being together in this world.

The Freshly Cut Grass had its World Premiere at the 2024 Tribeca Film Festival in the International Narrative Competition.

Upcoming Tribeca screenings:

Thursday, June 13 – 3:00 pm EST at AMC 19th St. East 6

Friday, June 14 – 3:15 pm EST at Village East by Angelika