Defining History ‘No Ordinary Life’ Interview With Documentary Filmmaker Heather O’Neill

“Cynde, Maria, Jane, Mary and Margaret took the images that defined history for their generation, yet their own stories have not been told, until now. The shifting scenes between the inhumanity and beauty they filmed, woven with their moments of humor, illustrate how they tried to cope with all they were witnessing. The wars and crises they covered produced images that can be difficult to watch, so I strived to create a balance of stories and images.” – Heather O’Neill

JUN 25, 2021

The feature documentary No Ordinary Life had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival during which I had the opportunity to speak with Heather O’Neill about her film and her passion to bring the lives of five extraordinary women from behind the camera to the screen.

About “No Ordinary Life”

In a field dominated by men, five pioneering photojournalists Mary Rogers, Cynde Strand, Jane Evans, Maria Fleet and Margaret Moth went to the frontlines of wars, revolutions and disasters. They made their mark by capturing some of the most iconic images from Tiananmen Square, to conflicts in Sarajevo, Iraq, Somalia and the Arab Spring uprising. In the midst of unfolding chaos, their pictures both shocked and informed the world.

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Heather O’Neill is an Emmy® and Peabody Award-winning journalist and documentary filmmaker. She produced the feature documentary Help Us Find Sunil Tripathi, and with CNN Presents, the award-winning documentary series, Heather directed and produced more than 20 projects around the world.

KOUGUELL: One poignant theme of the film was the idea of bearing witness.

O’NEILL: The genesis behind the film is that I wanted to show the world what these women experience. So often we generally don’t think about who is behind the camera. What motivated me to become a journalist was watching the protest in Tiananmen Square, and 20 years later I would meet Cynde Strand,, who was one of the photographers who stayed the night of the crackdown; I had never imagined at a young age that it was a woman behind the camera.

I wanted to make a film that allowed the audience to be immersed in their experience; the sights and the sounds of what was coming next. These women were incredibly driven, incredibly professional and their singular job was to bear witness and go to these conflicts and uprisings and revolutions to document what was happening and that was the main driver to go into these harrowing situations.

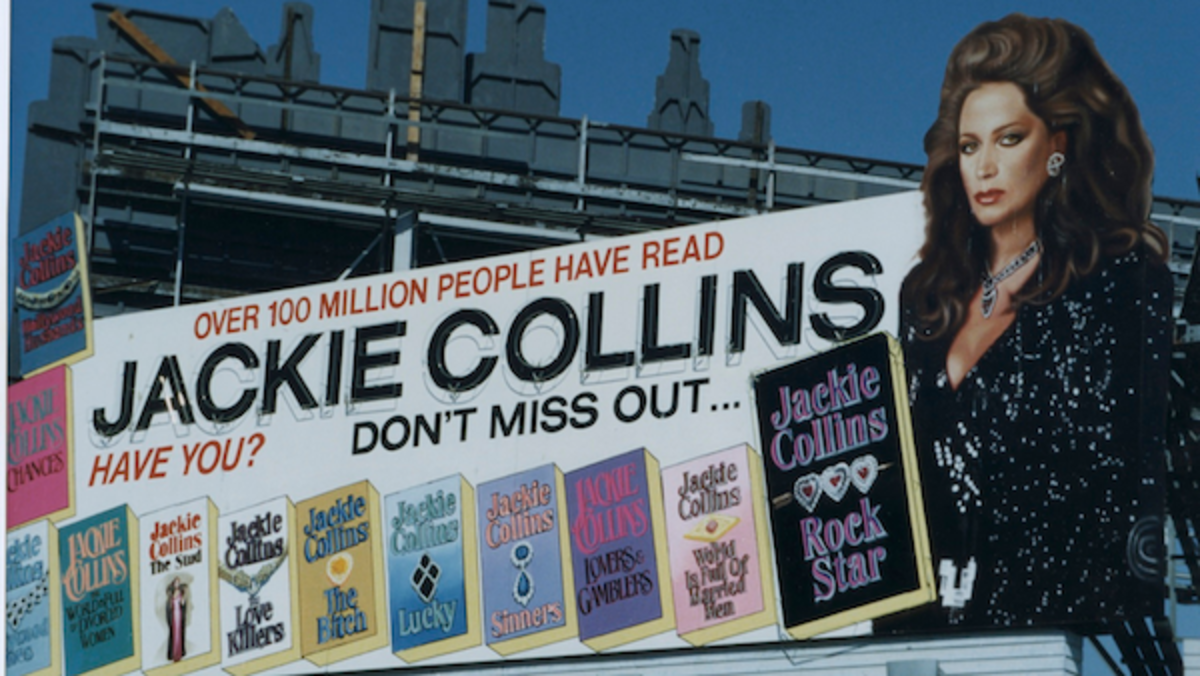

[The Making of an Icon ‘Lady Boss: The Jackie Collins Story’]

KOUGUELL: The camerawomen also talked about the female perspective in their work.

O’NEILL: They bristled at the question of ‘did you approach your stories differently as a woman?’ and I expected that and that’s fine. When we looked at some of their footage together, I noticed a bit of difference; there was a bit more intimacy or an instant rapport. Perhaps women are less threatening to certain subjects or in some cultures it’s more appropriate for a woman to approach another woman. I noticed a subtle difference in how they approached their filmmaking.

KOUGUELL: In an age when the media is often negatively portrayed by politicians and pundits, this film underscores the importance of storytelling.

O’NEILL: Yes. This was an untold story and that is what really drew me to it. Once I got to know these women and heard their stories collectively, I thought wow, you’ve been

told the history of your generation. I wanted to share their story. I didn’t grow up knowing super successful female photographers and in my career at CNN I would rarely see camerawomen and I felt it was a powerful story that needed to be told.

KOUGUELL: Tell me about the evolution of the project. Did you know the women beforehand?

O’NEILL: I first met Mary in Baghdad in 2006 and was struck by her tenacity and what an incredible professional and journalist she was. I worked with some of these women when I was at CNN. About four years ago I decided this would be a great story to do now. I think women’s stories are still somewhat untold and I think that’s changing, which is encouraging,

We approached all of them and talked about the footage shot and began to record their stories and developed that level of trust which is critical for a documentary director; people have to trust you to tell their story. They slowly began dropping off tapes to me. They had an incredible library of tapes, which told me that this just wasn’t an accident that someone decided to tell their story. I began the two-year process of screening the tapes along with my co-producer. The story began to come together. We interviewed with them, we filmed with them, and the scripting began.

KOUGUELL: When you planned out this documentary, did you work from an outline or any particular source material?

O’NEILL: For any documentary that I create I usually write a treatment, which you use to pitch when trying to get funding for a film. It is also my road map of where I knew I wanted to go. That was the first process, to have the story laid out in a three-to-five page treatment, and go on to do the pre-interviews with these women over Skype and over the phone, and begin to understand from their storytelling and for me, where we wanted to go with the narrative. We decided that we would weave the stories that they shot with their own backstories of behind the camera of what they were going through when they were actually filming.

KOUGUELL: Was there any reluctance from the camerawomen to speak with you?

O’NEILL: They are an incredibly humble group of women. I always wonder if it were a group of men, if it would be different. They witnessed a lot of difficult things and it was challenging at times to get them to talk about how they were feeling emotionally because there’s a little bit of guilt associated with being a journalist and being able to leave a situation where you know people can’t. They began to understand that we (the audience) have to understand their characters as human beings, too, not just journalists.

KOUGUELL: Advice for aspiring documentarians?

O’NEILL: Make your film, don’t wait for permission. If you have a story to tell, you’ll find a way to tell it. Getting this film made had its challenges. It’s a very long road and you have to be prepared to field a lot of nos. You’ll be surprised how many people want to help and be supportive.

About Screenwriting

About Screenwriting