In this wide-ranging interview, Susan Kouguell discusses with filmmaker Catherine Gund their respective work and shared artistic sensibilities in terms of employing nontraditional filmmaking structures, the inclusion of poetry in film, tackling challenging subject matter, and how to make it the most honest.

It was a pleasure to speak with Emmy-nominated and Academy-shortlisted producer, director, writer, activist and Aubin Pictures founder Catherine Gund about her new film Meanwhile. Gund’s media work focuses on strategic and sustainable social transformation, arts and culture, HIV/AIDS and racial, reproductive and environmental justice. Her films have screened worldwide and on many platforms. She won the 2023 Gracie Award for Documentary Producer.

Meanwhile is a docu-poem in six verses about artists breathing through chaos. In dynamic collaboration, Jacqueline Woodson (text), Meshell Ndegeocello (soundscape), Erika Dilday (support), M. Trevino (structure), and Catherine Gund (direction), combine artists’ expressions with historical and observational footage to unveil a rare cinematic meditation about identity, race, racism and resistance as they shape our shared breath.

In our wide-ranging interview, we discussed our respective work and shared artistic sensibilities in terms of employing nontraditional filmmaking structures, the inclusion of poetry in film, tackling challenging subject matter, and how to make it the most honest. As it turned out, we realized we were both fellows (several years apart) at the Whitney Independent Study Program, which further enlivened our talk.

Kouguell: How did Meanwhile evolve?

Gund: The film at its core is about community and about relationships, especially at a time when we were isolated and separated and left alone. There was so much loss and different kinds of loss. Obviously, the loss of people first and foremost, but we were also losing this whole sense of ourselves and our identity. And then this sense of our society.

It really started in June of 2020 when George Floyd was murdered. Also, I had a dear friend who is in the film named Ivy Joan Young, who had been sick for a while. She died in 2023. She became homebound with emphysema, which politically is hideous; menthol deadly cigarettes were being marketed to the African American community.

There was a lot about breath.

It was unmistakable that George Floyd was asphyxiated; he was strangled. People couldn’t breathe and they were dying. We were sharing one air. Then my other dear friend’s mother was also on oxygen and struggling to breathe. Breath at its core, was the genesis.

Kouguell: Tell me about your collaboration. Did the images or text come first, or did they work together from the start?

Gund: One of my oldest friends is Jacqueline Woodson, who wrote the narrative; we have always collaborated in some way or another. There was an opportunity here for us to try to deal with what was happening around us in the ways we knew how. Honestly, I imagined she was going to write a text and I would come up with some imagery but it became a bigger collaboration with many others, including Meshell Ndegeocello. It was a dynamic back and forth; it was not one or the other. I filmed on my little phone. It’s sort of a journal. I was inspired early on by Agnes Varda.

Kouguell: Me too! I was fortunate to interview Varda several times for this publication.

Gund: Varda’s documentary The Gleaners And I was definitely a main inspiration for me because I was collecting images. I’d see these men sweeping, and those images became such a dynamic part of the film, even at the end with the women finishing building their bed and they clean out the room. And then the archival footage of the one man in the 1950s sweeping in his baggy clothes, and he just looks right up at the camera.

I’ve had this approach to imagery – whether it’s a poem, a song or something that gives you a feeling just from its association – to let myself edit associatively and work associatively. Jackie would send me text, and it would inspire me to film in various locations where there were people of all races and classes. It wasn’t just about race, it was about class – strata.

Jesse [Krimes], the white guy in the film who has served so much time in incarcerated facilities who’s from Lancaster, Pennsylvania and not Amish, said: ‘I didn’t know what race was. Everybody was white, so there was nothing that made that edge.’

To me, that edge is again the association, associative editing and putting the edge between Jackie and I, between words and pictures, letting each other figure out what that association, and our association is.

Kouguell: These associations felt like a conversation. You were allowing the viewer to come to their own conclusions and to create their own narrative.

Gund: You’ll notice no one in the film ever says ‘that was racist’. In the extreme, that’s an opinion, right? We wanted it to be something where people were just experiencing what we were experiencing. And then realizing that they may have a different experience from someone else. That was a key takeaway for us.

We’re all seeing the same thing, we’re all in the same world of “meanwhile”, but also of our world. We have different choices we can make. But we still have the same materials to process.

Kouguell: How did you come about choosing the various artists to film?

Gund: The choice of artists really gets at the notion of community because we did not set out and make a list of artists and then go and talk to them. All of the artists are people I was in deep, sometimes decades-long, conversations with.

That sense of community has a kind of internal coherence or an internal sensibility. They are friends of mine and Jackie’s. It was more like one conversation led to another, and it turns out a couple of them are more well known or recognizable, and some are very new or are people that wouldn’t be considered artists at all.

What was interesting to me about working with them was that we. This is true for the whole film. I never wanted them to explain anything, not about our relationship, not about their work. I didn’t want them to say, ‘I use the color orange because sunsets are important to me’. I wanted to be in this “meanwhile” moment with them in between.

Kouguell: Tell me about incorporating archival footage.

Gund: I looked for footage that really engaged with ideas around race and racism, and places where races overlap because that’s where you learn about race and you learn about what we think about race. This is something Jackie and I were very committed to.

We were always trying to deeply contextualize them into our experience and not just pull them randomly out of nowhere. In the film you see Doc Rivers on the TV in an Ohio community center when he says, “I should just be a basketball coach, not an African American coach”.

It was a ripe time when we were making this film, because sh-t like that was happening all day. Every day. All the old stuff was coming back as being things we could use. Like the James Baldwin scene, it was really important to see that 50 years made no difference at all.

Kouguell: The film is structured with the six verses. It reminded me of symphonic movements, except generally there are only four movements with several exceptions, including Mahler’s 3rd Symphony.

Gund: I love what people bring to the film and point things out. I did obviously create a space where those associations made sense. There were some obvious yet unintentional associations related to breathing from some of the artists.

I had no reason for there to be specifically six, except that I had six ideas, and that’s what it broke into. To me it was really based on breath. The end point was our ability to go on; the vision and hope. The difference between being alive and being dead, is that you have one breath. But of course there’s more than one person.

The second is, who is the we? It’s more than one breath. Then, as soon as you have more than one person, it immediately devolves into a power struggle, a relationship, right? But then unrequited love. And then the reality – chaos, right? Yes, there is chaos but we made it an explicit goal to not re-traumatize and to not exhibit violence, but also not to brush everything under the rug. That is really the pivotal verse or movement. And then embracing the chaos. And then reclaiming the meanwhile.

Meanwhile opens Friday March 14 in selected theaters. Visit their website for more information about the film and screening schedule.

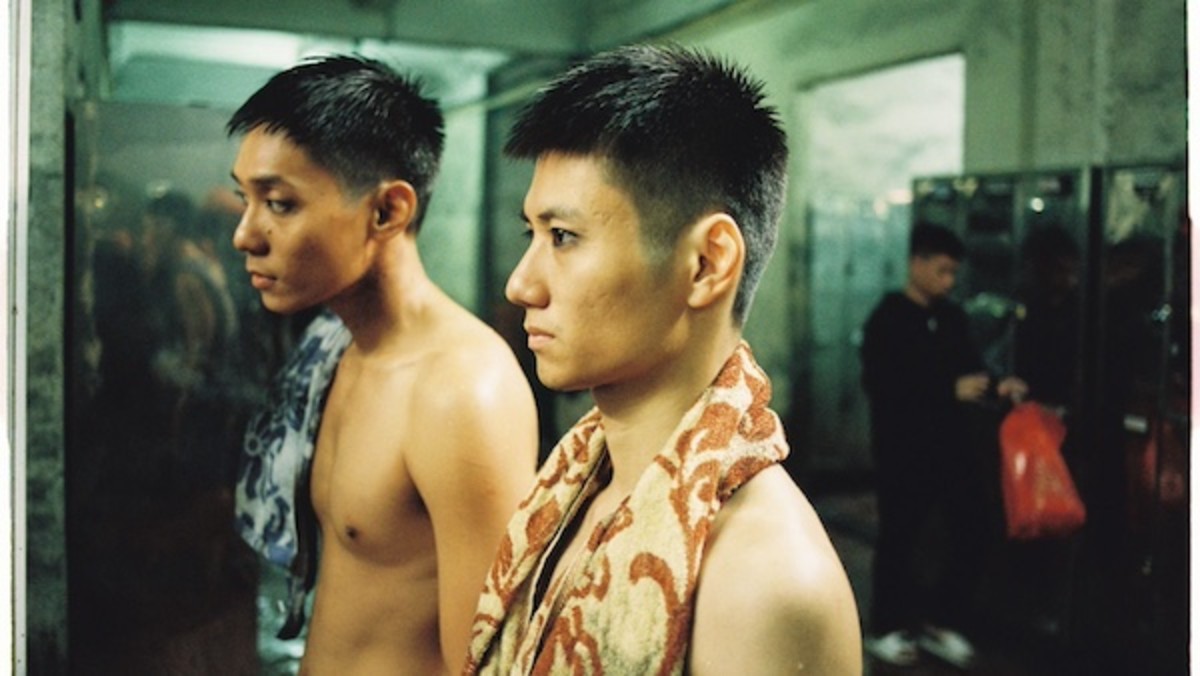

![[L-R] Ethan Herisse stars as Elwood and Brandon Wilson as Turner in director RaMell Ross’s NICKEL BOYS (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MjExMjc3ODAxMTc1NjU2MTI1/nb_fp_479_rgb-600.jpg)

![[L-R] Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba and Ariana Grande as Glinda in Wicked (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MjEwOTk5Njc4Njg5MzU1MzEx/wicked-universal.jpg)

![[L-R] Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba and Ariana Grande as Glinda in Wicked (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/ar_16:9%2Cc_fill%2Ccs_srgb%2Cfl_progressive%2Cg_faces:center%2Cq_auto:good%2Cw_640/MjEwOTc4Mzg3NDYyNzI3NjU3/241110-wicked-movie-doll-wm-417p-f678f6.jpg)

![[L-R] Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba and Ariana Grande as Glinda in Wicked (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MjEwOTc4NDA0Mzc0MTYxMzg1/241110-wicked-movie-600.jpg)

![[L-R] Elliott Heffernan as George and Saoirse Ronan as Rita in Blitz (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MjEwOTUyNTU0MDM5NzQ4NTg1/blitz__photo_0104.jpg)

![[L-R] Pastor Line Exercise; Artie Lindsay, Dr. James Stokes, Joan VanDessel, Ashlee Eiland, Tierra Marshall, Ben Kampmeier, Kim DeLong, Chase Stancle, Troy Hatfield, Andrew Vanover, Molly Bosscher and Cornelius Ting, LEAP OF FAITH (2024).](https://scriptmag.com/.image/t_share/MjEwNDY3Mzk5OTAyNzAxNTQ1/lof_photo-5.jpg)